Joiner played college football with the Grambling State Tigers and was a three-time, first-team all-conference selection in the Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC). He was selected as a defensive back in the fourth round of the 1969 NFL/AFL draft by the AFL's Houston Oilers, who soon returned him to the wide receiver position. Joiner played three and a half seasons each for the Oilers (1969–1972) and Cincinnati Bengals (1972–1975), missing substantial time through injuries with both teams.

Cincinnati traded Joiner to the Chargers, with whom he played for eleven seasons (1976–1986). He made the Pro Bowl in his first year with the team, but his role was reduced in the following two seasons, nearly leading him to retire as early as 1978. Joiner's career was revitalised once head coach Don Coryell installed his Air Coryell passing offense. He had three consecutive 1,000-yard receiving seasons from 1979–1981, making two further Pro Bowls (1979–1980) and the 1980 All-Pro team.

He retired with the most career receptions, receiving yards, and games played of any wide receiver in NFL history. He was noted for his precise route running, as well as his longevity and late-career success, with over half his catches coming after his 32nd birthday. Joiner went on to serve as a wide receivers coach for twenty-six years before retiring completely after the 2012 season.

Joiner graduated from Grambling in 1969 and was selected in the fourth round of the 1969 NFL/AFL draft with the 93rd overall pick by the AFL's Houston Oilers. A Corpus Christi Times draft review described him as a having "great speed (4.5 in the 40) and excellent hands." The Oilers drafted Joiner with intent to use him at defensive back; this upset Robinson, who stated his former player could "beat any defensive back one-on-one" in a press release urging Houston to keep him on offense. Joiner's own expectation was that he would "play a few years," qualify for an NFL pension and then move on to another career.

The Oilers eventually chose to play Joiner both ways as a rookie, installing him as their fourth wide receiver for the 1969 season. He was playing on offense when his rookie season was brought to an end by injury—he was tackled after making a catch in a week 7 victory over the Denver Broncos and suffered a compound fracture of the right arm. Head coach Wally Lemm described Joiner as a "fine young prospect" after the injury.

Joiner had another injury setback in 1970 when he broke an arm in the first preseason game. He missed the first five regular season games before returning to face the San Diego Chargers, producing 5 catches for 100 yards and scoring his first professional touchdown on a 46-yard pass from Jerry Rhome. He scored twice in a game against the Cincinnati Bengals later in the season, one of those on a career-long 87-yard touchdown catch.

Houston moved Joiner up in their depth chart by trading starting wide receiver Jerry LeVias before the 1971 season; general manager John W. Breen gave Joiner's performance in a preseason scrimmage as a reason for the trade. While the Oilers struggled for much of the season, they had one of the highest ranked passing attacks in the American Football Conference (AFC) and Joiner led the team in both receiving yardage and touchdowns.

Houston traded Joiner to Cincinnati six games into the 1972 season, on October 24; he and linebacker Ron Pritchard were sent to the Bengals in exchange for running backs Paul Robinson and Fred Willis. Joiner had been leading the Oilers in receiving with 16 receptions for 307 yards and 2 touchdowns, and had scored in his final game the day before the trade. He said, "I really didn't think it was me they were talking about. I was their leading pass receiver for two years and it really hurt me."

Houston traded Joiner to Cincinnati six games into the 1972 season, on October 24; he and linebacker Ron Pritchard were sent to the Bengals in exchange for running backs Paul Robinson and Fred Willis. Joiner had been leading the Oilers in receiving with 16 receptions for 307 yards and 2 touchdowns, and had scored in his final game the day before the trade. He said, "I really didn't think it was me they were talking about. I was their leading pass receiver for two years and it really hurt me."

Joiner said of his new team, "You come to a new situation and you may be a little scared, but everyone here has been friendly and it's been real good," adding that he found passes from the Bengals' quarterbacks to be thrown softer and to be easier to catch.

Cincinnati and Houston were scheduled to meet the Sunday after the trade. Joiner saw limited action with a single catch for 19 yards in a 30–7 win. Overall, he struggled to make an impact with his new team in 1972, catching only eight passes in eight games—he remained on the bench for the entirety of two of these. The Cincinnati Enquirer described him as a "disappointment" who "never quite measured up."

Joiner's progress was praised by offensive assistant coach Bill Walsh in the build-up to the 1973 season, with Walsh noting a particular improvement in accurate route running. Nonetheless, he entered the 1973 season with his position in the team under threat after the Bengals selected another wide receiver, Isaac Curtis, in the first round of the NFL draft; Curtis was expected to start as a rookie. Joiner suffered another injury setback in preseason, this time to his knee, and began the regular season on the inactive list. Head coach Paul Brown was impressed by his attitude as he fought to regain fitness after the injury, saying "No man ever worked harder or gave it more to get himself back in shape." Joiner returned to face the Cleveland Browns after missing three games but was immediately injured again; he caught a 26-yard pass on the Bengals' first play from scrimmage but suffered a fractured collar bone while being tackled and was believed to be out for the year.

Joiner returned sooner than expected, missing six further games before beginning a consecutive appearance streak that would last for over 13 years. Quarterback Ken Anderson praised Joiner's impact, saying that having both he and Curtis on the field stretched the opposing defense, who could not double cover both of them. Joiner finished the season with 13 catches for 134 yards from his five appearances. The Bengals were successful as a team, winning the AFC Central division with a 10–4 record. Joiner's first playoff game ended in a 34–16 defeat to the Miami Dolphins. The Bengals' passing attack was largely shut down, and he caught only two passes for 33 yards.

Cincinnati gave Joiner a new multi-year contract in the run-up to the 1974 season. He scored his first Bengals touchdown in week 5, a 65-yarder against Cleveland. He shared time with Chip Myers as Curtis' partner during the year.

Brown planned to use Joiner together with Myers and second-year receiver John McDaniel as a trio of partners for Curtis in 1975. He was the most successful of the three as the season progressed, posting new career bests of 37 receptions for 726 yards, an average of 19.6 yards per catch. On November 23, 1975, he set a Bengals then-single-game record with 200 receiving yards in a 35–23 loss to Cleveland; it would remain his personal career high.

Cincinnati won a wild card spot in the playoffs with an 11–3 record. They again lost in the first round, this time 31–28 to the Oakland Raiders. Joiner scored his first postseason touchdown as the Bengals came close to rallying from seventeen points behind in the final quarter—he said, "We should have won the ball game, we just ran out of time." It was his final game as a Bengal.

On April 1, Cincinnati traded Joiner to the San Diego Chargers for defensive end Coy Bacon. Brown acknowledged that Joiner was coming off a good year, but identified the defensive line as a stronger area of need for his team. Joiner was happy to reunite with Walsh, who had just joined the Chargers as their offensive coordinator. Chargers quarterback Dan Fouts was impressed by his new receiver in preseason: "I love Charlie Joiner. He has a knack for finding the open spot."

Joiner became the Chargers' leading receiver during a successful 1976 season with the team. He had a run of four consecutive 100-yard games early in the year, and secured his first 1,000-yard receiving season with two games to spare. He finished the year with 50 receptions for 1,056 yards (the third most in the league, and 285 more than Curtis had in Cincinnati) while averaging 21.1 yards per catch, and was named second-team All-Pro by the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) at season's end.

The trade for Joiner benefited both teams in the short term, as both he and Bacon were named to the Pro Bowl and voted MVP by their respective teams that year. Beyond 1976, Bacon only played one more year in Cincinnati, while Joiner's career with the Chargers covered a further decade.

Joiner gave some thought to retirement before committing to play the 1977 season. He was reunited with his Grambling quarterback James Harris on the field, as Fouts was holding out through much of the season. Joiner was often double covered as newly acquired receiver Johnny Rodgers was injured, and their No. 1 draft pick from the year before, running back Joe Washington, was recovering from knee issues. Joiner finished with 35 catches, 542 yards and 6 touchdowns, short of his 1976 performance in all three statistics but still enough to led all Chargers wide receivers.Ray Perkins became the Chargers' offensive coordinator in 1978, their third offensive coordinator in three years. He emphasized using running backs as possession receivers and rookie No. 1 pick John Jefferson as the deep threat while phasing out Joiner, who had undergone offseason knee surgery. He informed head coach Tommy Prothro before the season that he was considering retirement, but Prothro was able to persuade him to continue. Don Coryell became San Diego's head coach in 1978, replacing Prothro midseason; Coryell had a reputation as an offensive strategist, but largely stuck with Perkins' system in 1978. Joiner struggled with post-surgery knee problems during the year and finished with 33 receptions, two fewer than in 1976 despite the regular season increasing from fourteen games to sixteen.

In the 1979 season, Joiner featured heavily in the pass-based offense known as Air Coryell. The Chargers bolstered their receiving corps entering the season by using their first-round draft pick to select tight end Kellen Winslow. Coryell also hired Joe Gibbs as the new offensive coordinator that season after Perkins left for the New York Giants. They noticed that Joiner had been getting open the year before, and envisioned him as a key to their offense.

It was a successful regular season for the Chargers, as they posted a 12–4 record and earned their first divisional title in 14 years. Joiner played a key role in the division-deciding game, a 17–7 win over the Denver Broncos in the regular-season finale. He was forced back to the locker room twice during the game with injuries, but returned to the field bandaged both times. He sustained a concussion during the game and finished it with stitches over one eye, as well as hip and thigh injuries. Joiner finished the game with 3 catches for 58 yards and the game-winning touchdown. It was an inspirational performance with Jefferson unable to play and John Floyd, the Chargers only other receiver, being just a rookie; Coryell later remembered it as "The Charlie Joiner Game."

Joiner finished second in the AFC in receptions to Baltimore's Joe Washington, his former Chargers teammate, with a career-high 72 catches covering 1,008 yards and four touchdowns. His reception total was the most by a Charger since Lance Alworth's 73 in 1966, and the most by a player Joiner's age (32) in NFL history at that time. Joiner was the third player in league history to catch 70 or more passes after age 30, joining Don Maynard and Ahmad Rashad, who were each 30. He was named to the Pro Bowl, replacing an injured Lynn Swann, who himself was a replacement for Steve Largent. Joiner was the oldest player in the all-star game.

Joiner's third playoff game ended in another defeat; his former team the Oilers overcame key injuries to surprise San Diego 17–14 in their own stadium. A disappointed Joiner commented: "I think we took it for granted... You got to fight in this game. We let them take it away from us. They wanted it more than we did."

Joiner had again expected to retire after the previous season, but returned in 1980 saying he wanted "one more shot at the Super Bowl." He had a career-high 10 catches in one game in a 44–7 win over the New York Giants, accounting for 171 yards and a touchdown. Joiner finished the year with 71 receptions for 1,132 yards, and teamed with Jefferson and Winslow to become the first trio of receivers on a team to reach 1,000 yards in the same season. The three were all named first-team All-Pro by the Associated Press.

The Chargers won their division again, this time with an 11–5 record. In the divisional playoffs, Joiner's 9-yard touchdown catch from Fouts began a comeback that saw the Chargers turn a 14–3 halftime deficit into a 20–14 victory, Joiner's first in the playoffs. San Diego progressed to the AFC championship game, where Joiner led the team with 6 catches for 130 yards and two touchdowns, but could not prevent a 34–27 home defeat to the Raiders. Reflecting on a second consecutive season of being eliminated at home, Joiner said, "We have to think about opportunities. We really missed the last two years."

Joiner once again considered retirement before the 1981 season, saying "Frankly, I don't know how much longer I can play. I feel my skills have diminished." Nonetheless, he continued his career, beginning the season as the Chargers' top wide receiver due to Jefferson holding out and eventually being traded. In San Diego's opening game at Cleveland, Joiner caught 6 passes for 191 yards, which would be his best total with the Chargers. This prompted Fouts to say, "I don't why he's so much better than he was when I first saw him, but he is. I've never seen him better." After another strong performance in week 2, Joiner already had 13 catches for 357 yards on the season, and felt his knees to be in better condition than past seasons. His production decreased in the following weeks as opposing defenses double covered him, but the addition of Wes Chandler to replace Jefferson relieved that pressure. Joiner finished with 70 catches, making him the first receiver with at least 70 catches in three consecutive NFL seasons. He also had a team-leading and career-high 1,188 yards receiving, and the Chargers won their third consecutive AFC West title with a 10–6 record.

In the divisional playoffs, Joiner played a key role in San Diego's 41–38 overtime win over the Miami Dolphins, a game that became known as The Epic In Miami. He caught 7 passes for 108 yards, including a 39-yard reception on the penultimate play of the game set up Rolf Benirschke's game-winning 29-yard field goal. The Chargers advanced again to the conference championship, but lost 27–7 to Joiner's former team Cincinnati in a game later known as the Freezer Bowl due to frigid gameday conditions.

Joiner committed to another season in July, signing a new contract. The 1982 season was reduced to nine games by a players' strike. Joiner had no touchdowns in the regular season, though he did produce three 100-yard games.

San Diego finished 6–3, making the playoffs for the last time in Joiner's career. They won their first game 31–28 at the Pittsburgh Steelers, but lost the next 34–13 in Miami, with their powerful offense largely shut down. Joiner scored his only touchdown of the season during the Miami defeat. He said, "The Chargers are human. You can't ask everything of us, every game."

During the offseason Joiner intimated that his decision on whether to continue his career might rest on whether Fouts, a free agent, negotiated a new contract with the Chargers. Fouts did eventually sign, and Joiner was back for another season.

The Chargers had a disappointing 1983 campaign; Fouts missed time through injuries, and they finished 6–10. Joiner played the full season despite cracked ribs, he caught 65 passes for 960 yards and 3 touchdowns, and was voted both the most valuable and most inspirational Charger by his teammates. His late-career surge had seen Joiner catch 314 passes in the past five seasons after only catching 282 in his first ten.

Joiner quickly expressed an interest in returning for the 1984 season, and said that he was "kind of looking forward to camp." He nonetheless did not attend his first mandatory practice, as he was holding out for a two-year contract and the Chargers were only offering him one year. Winslow said of his absence, "It's like there's a missing link, the chemistry isn't there. It's as if you're missing an ingredient." The holdout lasted only six days before Joiner agreed to a one-year contract. He entered the season needing 52 receptions to break Charley Taylor's NFL record of 649 for a career.

Joiner made little impact during the early part of the season, with only eight catches during the first four games; in week 4 against the Raiders he had no catches at all, ending a streak of 85 consecutive games with a catch (78 regular season, 7 postseason). He improved enough to finish with 61 catches on the year.

Joiner passed Taylor as the career leader in receptions on November 25, 1984, breaking the mark with 6 catches for 70 yards and a touchdown in a 52–24 loss against the Steelers. The record-breaking 650th catch was a 3-yarder from backup quarterback Ed Luther late in the game. Joiner expressed disappointment that the landmark had come in an away game, in a loss, and that Fouts hadn't thrown the record-breaking pass.

During the offseason Joiner signed another one-year contract, committing to a tenth year with the Chargers. He stated in training camp that he considered himself "on the bubble" as a player who might struggle to maintain a place in the team at the expense of younger receivers. Joiner continued to play in every game, and passed Jackie Smith's record of 210 appearances at a receiving position early in the season. He finished the 1985 season with 59 catches for 932 yards, and tied his career high by scoring 7 touchdowns.

Joiner signed another one-year contract, and entered the 1986 season only 128 receiving yards behind Don Maynard's NFL record of 11,834 for a career. He would turn 39 during the course of the season and was the second-oldest active player behind Jeff Van Note of the Atlanta Falcons, as well as the oldest wide receiver in league history.

He surpassed Maynard's record of receiving yards in a week 5 away game against the Seattle Seahawks. The record-breaking catch was a 20-yarder from Fouts during the 3rd quarter of a 33–7 defeat; the game was halted briefly and Joiner got a standing ovation from the Seattle crowd. Joiner broke his right hand late in the season. In week 15, he was available to play in what would have been his final home game, but was kept on the sidelines by new head coach Al Saunders due to his injury. It was the first game he had missed since 1973 with the Bengals, and broke a 194-game regular season appearance streak. Joiner was disappointed, but said that the younger receivers had practiced all week for the game and it would have been unfair to them if he had played. Saunders expressed regret for not using him, saying that the Joiner's streak and potential last home game didn't cross his mind. Joiner did play the following week, ending his career with 3 catches for 25 yards in a 47–17 defeat at Cleveland.

Joiner finished the year with 34 catches, his least productive season since 1978, and retired from playing after the season. He said, "I'd thought about it for about eight or nine years and I finally did it. I'm 39 and that's too old to be playing football for a wide receiver. I've had a great career, I think, and I'm just proud of the fact that I finished No. 1, even though it probably won't last that long."

Joiner was the last active player from the AFL. He finished his 18 AFL/NFL seasons with 750 receptions for 12,146 yards, averaging 16.2 average per catch, and 65 touchdowns. He caught 586 passes in 11 seasons with San Diego after totaling 164 in seven seasons with Houston and Cincinnati. Joiner had 50 or more catches in seven seasons, five with 60 or more, and three with at least 70 with the Chargers. He retired as the then-NFL leader in career receptions and receiving yards. At the time, he also played the most seasons (18) and games by a wide receiver (239). At age 39, Joiner also retired as the oldest wide receiver in NFL history, Joiner had 530 receptions after he was 30 years old, including 396 starting from the 1980 season, during which he turned 33. He credited his success and longevity to Coryell: "Thanks to Coach Coryell’s offense and his revolutionary passing game, he prolonged my career, from the day I got to the Chargers until the day I retired. I will forever be grateful to him and what he did for the game of football."

Joiner excelled despite neither being among the quickest nor most talented receivers in the NFL. Throughout his career, he was overshadowed by more glamorous receiving mates, including LeVias and Ken Burrough in Houston, Curtis in Cincinnati, and Jefferson, Chandler, and Winslow with San Diego. In addition to good health and longevity, Joiner was an intelligent player and precise pass route runner, capable of changing direction without sacrificing speed due to a short stride and low centre of gravity. He had a tendency to fumble while with the Bengals, but fixed the problem and seldom fumbled while in San Diego. Joiner rarely ran deep routes, specialising in running inside patterns and making tough catches in traffic. He became aware early in his time in San Diego that he no longer had the sprinting speed of his youth, and compensated with an improved knowledge of defenses brought on by experience. Quiet and modest as an individual, Joiner was voted the Chargers' most inspirational player seven times by his teammates.

Hall of Fame coach Walsh called Joiner "the most intelligent, the smartest, the most calculating receiver the game has ever known." Gibbs, his offensive coordinator in San Diego, praised Joiner as "a totally dedicated guy who was just a great producer." "Without question, he is the finest technician—running routes and reading coverages—in the National Football League", said Ernie Zampese, the Chargers' receiving coach. Bengals teammate Bob Trumpy praised Joiner's work ethic, saying, "You know why he's caught all those balls? Because he's busted his tail in every practice, on every play in practice. Whatever quarterback he's been with has known that Charlie will be there, every time. He trusts Charlie." Joiner was Fouts' favorite receiver on third down. "All I’m trying to do out there is look for a port in a storm. He’s the port. Having Charlie is like having a fail-safe button," said Fouts.

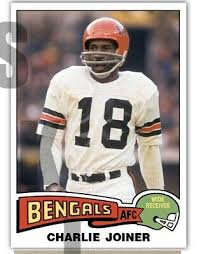

Joiner was inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame in 1990. He was voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1996, becoming the third Grambling player to be selected. In 1999, he was ranked No. 100 on The Sporting News's list of the 100 greatest football players, while a 2019 USA Today article ranked him as the ninth-best player in Chargers history. He was inducted into the Black College Football Hall of Fame in 2013. The Chargers inducted Joiner into their hall of fame in 1993 and retired his No. 18 in 2023.

In 1987, Saunders hired Joiner as an assistant coach working with wide receivers. He was retained by the following head coach, Dan Henning, but Henning's entire coaching staff were dismissed following the 1991 season, ending Joiner's sixteen-year run with the team as a player and coach. He joined the Marv Levy's Buffalo Bills shortly afterwards, again serving as a wide receiver coach, then moved on to take the same role with the Kansas City Chiefs in 2001. Joiner stayed with the Chiefs for seven seasons before losing his job with them in 2008; he re-joined the Chargers three weeks later for final stint working with their receivers. Joiner spent five more years in San Diego, then announced his retirement at the age of 65, saying football was "definitely a young man's game."

Joiner's retirement ended a 44-year professional career, eighteen as a player and twenty-six as a position coach. Twenty-one of those years were spent with the Chargers.

After leaving the Oilers, Joiner continued to live in Houston throughout the rest of his playing career, only moving to Rancho Bernardo in San Diego when he joined the Chargers' coaching staff. He has an accountancy degree from his time in college, and worked part time for Gulf Oil during the offseason for ten years. Joiner was unusual in not employing a sports agent, as his knowledge of finance allowed him to manage his own contract negotiations.

Joiner is married and has two daughters.