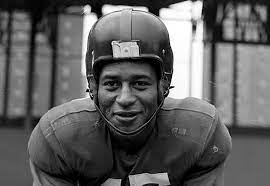

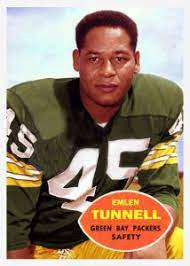

Elroy Leon "Crazylegs" Hirsch was an American professional football player, sport executive and actor. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1967 and the College Football Hall of Fame in 1974. He was also named to the all-time All-Pro team selected in 1968 and to the National Football League 1950s All-Decade Team.

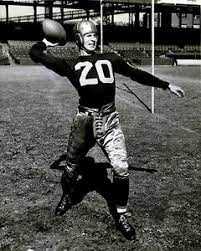

A native of Wausau, Wisconsin, Hirsch played college football as a halfback at the University of Wisconsin and the University of Michigan, helping to lead both the 1942 Badgers and the 1943 Wolverines to No. 3 rankings in the final AP Polls. He received the nickname "Crazylegs" (sometimes "Crazy Legs") for his unusual running style.

Hirsch served in the United States Marine Corps from 1944 to 1946 and then played professional football in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) for the Chicago Rockets from 1946 to 1948 and in the NFL for the Los Angeles Rams from 1949 to 1957. During the 1951 season, Hirsch helped lead the Rams to the NFL championship and tied or broke multiple NFL records with 1,495 receiving yards, an average of 124.6 receiving yards per game (still the third-highest season average in NFL history), and 17 touchdown receptions.

Hirsch had a brief career as a motion picture actor in the 1950s and served as the general manager for the Rams from 1960 to 1969 and as the athletic director for the University of Wisconsin from 1969 to 1987.

Hirsch enrolled at the University of Wisconsin in the fall of 1941 and played on the school's freshman football team. As a sophomore, Hirsch starred as a halfback for the 1942 Wisconsin Badgers football team that compiled an 8–1–1 record, defeated reigning national champion Ohio State (17–7), lost only one game to Iowa (0–6), tied with Notre Dame (7–7), and was ranked No. 3 in the final AP Poll. At the end of the season, Hirsch was selected by the Associated Press (AP) as a first-team halfback on the 1942 All-Big Ten Conference football team. In the three years prior to 1942, Wisconsin's football team had gone 8–15–1, and the program had been in decline since 1932. During the 1942 season, Hirsch's only season with the Wisconsin football team, he was a triple-threat man who totaled 767 rushing yards on 141 carries, completed 18 passes for 226 yards, punted four times for an average of 48.8 yards, intercepted six passes, and returned 15 punts for 182 yards. He rushed for a high of 174 yards against Missouri.

Hirsch acquired the "Crazylegs" nickname because of his unusual running style in which his legs twisted as he ran. According to one version, after watching Hirsch play in an October 17, 1942, game against the Great Lakes Naval Station, sportswriter Francis J. Powers of Chicago Daily News wrote: "His crazy legs were gyrating in six different directions, all at the same time; he looked like a demented duck." According to another version, he acquired the nickname in high school when fans in Wausau watched "the tall, slim Hirsch" run as "his legs seemed to whirl in several directions."

Hirsch's father later recalled: "We lived two miles from school. Elroy ran to school and back, skipping and crisscrossing his legs in the cement blocks of the sidewalks. He said it would make him shiftier." Hirsch himself recalled: "I've always run kind of funny because my left foot points out to the side and I seem to wobble." He embraced his nickname, saying in interviews, "Anything's better than 'Elroy'."

In the 1970s, Hirsch filed a lawsuit asserting legal ownership of the "Crazylegs" name. He sued S. C. Johnson & Son for its marketing a shaving gel for women's legs under the brand name "Crazylegs". In a 1997 decision, the Wisconsin Supreme Court held that Hirsch's complaint set forth a viable claim for invasion of Hirsch's common law right of privacy.

In January 1943, Hirsch enlisted in the United States Marine Corps and was transferred to the University of Michigan as part of the V-12 Navy College Training Program. In early September 1943, he broke the record at Michigan's Marine Corps training center, completing a 344-yard obstacle course in one minute and 31 seconds. He was the starting left halfback in the first seven games of the season for Fritz Crisler's 1943 Michigan Wolverines football team that compiled an 8–1 record and was ranked No. 3 in the final AP Poll. After watching Hirsch in pre-season practice, Associated Press football writer Jerry Liska referred to "squirming Elroy Hirsch" as "Wisconsin's gold-plated wartime gift to Michigan." Hirsch and Bill Daley (a V-12 transfer from Minnesota) became Michigan's most powerful offensive weapons during the 1943 season and were dubbed Michigan's "lend-lease backs."

In his first game for Michigan, Hirsch returned the opening kickoff 50 yards, scored two touchdowns and intercepted a pass. He scored five touchdowns in Michigan's first three games and threw for a touchdown in the fourth game against Notre Dame. On October 11, 1943, Hirsch scored three touchdowns, including a 61-yard reverse around the right end, and intercepted a pass to help Michigan to its first victory over Minnesota since 1932. Due to a shoulder injury, he appeared only briefly as a backup to kick for extra points in the final two games of the season, but he still led the Wolverines in passing, punt returns, and scoring.

During the 1943–1944 academic year, Hirsch also won varsity letters in basketball (as a center), track (as a broad jumper), and baseball (as a pitcher), becoming the first Michigan athlete to letter in four sports in a single year. He averaged 7.3 points per game for the 1943–44 Michigan Wolverines men's basketball team, compiled a 6–0 record as a pitcher for the Michigan baseball team, placed third in the long jump in the 1944 indoor championship, and led all three teams to Big Ten Conference championships. On May 13, 1944, Hirsch starred in two sports in the same day, winning the broad jump with a distance of 24 feet, 2-1/4 inches at a track meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and then traveling to Columbus, Ohio, where he pitched a one-hitter to give Michigan's baseball team a 5–0 victory over Ohio State.

In June 1944, Hirsch and 23 other Michigan athletes were transferred to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, South Carolina. In the fall of 1944, Hirsch was assigned to Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune where he played for the base football team. In the spring of 1945, he was stationed at Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in May 1945.

Hirsch remained with the Marine Corps in the fall of 1945 and played for the Marine Corps football team at the Marine Corps Air Station El Toro in California. In September 1945, he scored four touchdowns for the El Toro team in a game against the Los Angeles Bulldogs.

Hirsch was discharged from the military in May 1946. On August 23, 1946, he led the college all-star team to a 16–0 victory over the NFL champion Los Angeles Rams in the Chicago College All-Star Game. Hirsch was named the game's outstanding player, and the Los Angeles Times described his performance in the game as a "one-man show" after he scored the game's only touchdowns, including a 68-yard touchdown sprint, for the college squad. Hirsch later described the game as his greatest athletic thrill.

In January 1945, the Cleveland Rams selected Hirsch in the first round (fifth overall pick) of the 1945 NFL Draft. In May, he announced that he would not sign a contract with the Rams, stating that he intended to return to the University of Wisconsin after his discharge from the military.

He ultimately opted not to play in the NFL, instead playing for the Chicago Rockets of the All-America Football Conference (AAFC). Hirsch chose the Rockets because they were coached by Dick Hanley, who had been Hirsch's coach with the El Toro Marines team. Hirsch played three seasons with the Rockets from 1946 to 1948. During those three years, the Rockets compiled a 7–32 record and won only one game in each of the 1947 and 1948 seasons. Hirsch later said the decision to sign with the Rockets was the worst decision he ever made.

In a remarkable display of versatility, Hirsch appeared in all 14 games for the Rockets in 1946, contributing 1,445 yards: 384 kickoff return yards and one touchdown; 347 receiving yards and three receiving touchdowns; 235 punt return yards and one touchdown; 226 rushing yards and one rushing touchdown; 156 passing yards and one passing touchdown; and 97 return yards on six interceptions.

In September 1947, Hirsch caught a 76-yard touchdown pass for an AAFC record. However, injuries limited Hirsch to five games in 1947. He was described in December 1947 as probably "the highest paid waterboy in pro football."

In the fifth game of the 1948 season, Hirsch sustained a fracture on the right side of his skull after being kicked in the head during a game against the Cleveland Browns. Hirsch did not return to action during the 1948 season, totaling 101 receiving yards and 93 rushing yards in five games.

In June 1949, Hirsch alleged that the Hornets (the Chicago Rockets were renamed the Hornets in 1949) had breached a contractual obligation to pay him a bonus and sought a release to allow him to play for the Green Bay Packers. However, the Los Angeles Rams held Hirsch's NFL rights having selected him in the 1945 NFL Draft, and Hirsch was therefore unable to sign with the Packers. Instead, he signed with the Rams in July 1949. Hirsch earned $20,000 a year from the Rams, following a bidding war with the Hornets. However, after the 1949 season, the AAFC folded, and the Rams reduced his salary with the competition from the AAFC gone. During his career with the Rams, Hirsch never again attained the salary level he was paid as a rookie.

Rams head coach Clark Shaughnessy played Hirsch at the end position. In his first game for the Rams, a 27–24 victory over the Detroit Lions, Hirsch scored two touchdowns, including a 19-yard touchdown reception from Norm Van Brocklin. Over the course of the 1949 season, Hirsch tallied 326 receiving yards, 287 rushing yards, and 55 return yards on two interceptions. During the 1949 season, Hirsch also became one of the first NFL players to wear a plastic helmet. After Hirsch sustained a second head injury (having previously suffered a skull fracture in 1948), Rams coach Shaughnessy had a special, 11-ounce helmet designed for Hirsch, using a strong, light plastic that had been used previously in the construction of fighter planes.

In the opening game of the 1951 season, Norm Van Brocklin passed for an NFL record 554 yards, including 173 yards and four touchdown passes to Hirsch. During the season, Hirsch, Van Brocklin, Bob Waterfield, and Tom Fears (all four of whom have been inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame) led the Rams to an 8–4 record and a victory over the Cleveland Browns in the 1951 NFL Championship Game. Easily the best year of his career, Hirsch tied or broke multiple NFL receiving records in 1951. Hirsch set a new NFL record with 1,495 receiving yards. Despite the fact that the NFL season consisted of only 12 games in 1951, Hirsch's single-season receiving record stood for nearly 20 years, until the merger of the AFL and the NFL. Hirsch's average of 124.6 receiving yards per game also set a new NFL record. Through the end of the 2015 NFL season, only two players have exceeded this record. Hirsch also had 17 touchdown receptions in 1951, tying an NFL record set by Don Hutson in 1942. Despite the expansion of the NFL schedule to 16 games, the Hirsch/Hutson mark of 17 touchdown catches lasted until the 1980s, and only four players through the end of the 2015 NFL season have exceeded the mark. On his 17 touchdown catches, Hirsch averaged 51.2 yards, including a 91-yard reception that was the longest of the year in the NFL. For this reason, Bob Oates of the Los Angeles Times wrote that, even in the era of Jerry Rice, Hirsch "remains the greatest long-distance receiving threat of all time." Hirsch's 66 receptions also led the NFL in 1951 and was the fifth highest total in NFL history to that date.

After the 1951 season, Hirsch finished second behind Otto Graham in voting conducted by the United Press (UP) for the NFL Player of the Year award. He was also selected as a first-team All-Pro player by both the Associated Press (AP) and the UP. He was also selected to play in the Pro Bowl each year from 1951 to 1953. Hirsch had another strong season in 1953, leading the NFL with a career-high average of 23.6 yards per reception. He also finished second in the NFL with 941 receiving yards in 1953 and was selected as a first-team All-Pro by the AP and a second-team All-Pro by the UP.

Hirsch continued to play for the Rams through the 1957 season. He announced his retirement as a player at age 34 in January 1958. In nine years with the Rams, Hirsch totaled 343 receptions for 6,299 yards and 53 touchdowns. He also gained 317 rushing yards with the Rams.

After retiring from football, Hirsch accepted a job with Union Oil to replace Bob Richards as the sports director of Union Oil Co.'s 76 Sports Club and the host of its Thursday evening sports television show. He also hosted a daily sports commentary show on KNX radio from 1961 to 1967. During the 1950s, Hirsch also starred in several motion pictures.

In March 1960, Hirsch signed a three-year contract to serve as the general manager of the Los Angeles Rams; he replaced Pete Rozelle as the Rams' general manager after Rozelle was hired as NFL commissioner. The Rams began the 1960s in the lower tier of the NFL, compiling a losing record each year from 1959 to 1965. As general manager, he was in charge of scouting, the college draft, and negotiating player and coach contracts. During his tenure as general manager, the team drafted numerous talented players, including quarterback Roman Gabriel (first-round pick in 1961), Deacon Jones (14th-round pick in 1961), and Merlin Olsen (first-round pick in 1962), player who helped the Rams improve to 11–1–2 in 1967 and 10–3–1 in 1968. In 1963, after Dan Reeves acquired outright ownership of the Rams, Hirsch's title was changed to assistant to the president. He continued to serve as Reeves' assistant through the 1968 season.

In February 1969, Hirsch was hired away from the Rams to serve as the athletic director at the University of Wisconsin. Within four years, he had raised home attendance at football games from an average of 43,000 to 70,000 per game. During his tenure as athletic director, the number of sports offered by the UW athletics department doubled and the Badgers won national titles in ice hockey, men's and women's crew, and men's and women's cross country. However, the program also had problems with recruiting violations and a fundraising controversy. Hirsch announced his resignation as Wisconsin's athletic director in December 1986; the resignation became effective at the end of June 1987. In July 1987, he was hired to do color commentary on radio broadcasts of Wisconsin football games.

Hirsch died of natural causes at an assisted living home in Madison, Wisconsin in January 2004 at age 80.

Sources

https://www.pro-football-reference.com/

https://www.profootballarchives.com/index.html

https://americanfootballdatabase.fandom.com/wiki/Football_Wiki

https://www.gridiron-uniforms.com/GUD/controller/controller.php?action=main

https://www.profootballhof.com/hall-of-famers/

"Elroy Hirsch". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

"Marathon County Historical Society: People of Marathon County". Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2016. "Elroy was born in Wausau on June 17, 1923. His adoptive parents, Otto and Mayme Hirsch were German–Norwegians, his father a worker in a local iron works."

1930 Census entry for Otto Hirsch and family. Otto, age 42, born in Wisconsin, foreman in iron works. Son Elroy, age six, born in Wisconsin. Census Place: Wausau, Marathon, Wisconsin; Roll: 2582; Page: 15A; Enumeration District: 0066; Image: 959.0; FHL microfilm: 2342316. Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2002.

"Wausau Ace Leads Scorers". The Rhinelander (Wis.) Daily News. October 4, 1939. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Hirsch Runs Wild; Cards Swamp Rapids". The Rhinelander (Wis.) Daily News. October 23, 1939. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Shav Glick (January 29, 2004). "Elroy 'Crazy Legs' Hirsch, 80; Football Hall of Famer Was An L. A. Rams Star". Los Angeles Times. p. B12 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Bob-Tales". The Rhinelander (Wis.) Daily News. October 15, 1941. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"1942 Wisconsin Badgers Schedule and Results". SR/College Football. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

Burton Benjamin (October 7, 1942). "Sophomore Elroy Hirsch Is Wisconsin's Frank Merriwell (NEA story)". Dixon (IL) Evening Telegraph. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Tony Wirry (October 31, 1942). "Badgers Discover a Climax Runner; He's Elroy Hirsch". East Liverpool (OH) Review. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Len Wagner (April 6, 1969). "He wasn't sure he really wanted the UW job". Green Bay Press-Gazette. pp. 2–4.

"Badgers Put Four On AP All-Big Ten Team". The Akron Beacon Journal (AP story). November 29, 1942. p. 4C – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Patrick Dorn (May–June 1987). "Crazy Legs Heads Into the open". The Wisconsin Alumnus. pp. 4–5.

"Elroy Hirsch". University of Wisconsin Sports News Service. February 21, 1969. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

Anderson, Dave (2005). University of Wisconsin Football. Arcadia Publishing. p. 61.

Wallace, William N. (January 29, 2004). "Crazylegs Hirsch, 80, Rams' Big-Play Receiver, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

College Football Hall of Fame profile

Hirsch v. S. C. Johnson & Son, 280 N.W.2d 129 (1979).

"Elroy Hirsch". University of Wisconsin. 1969.

"Hirsch Continues Record-Breaking In Marine Center". The News-Palladium. September 10, 1943. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"1943 Football Team". University of Michigan, Bentley Historical Library. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

Jerry Liska (September 1, 1943). "Hirsch, Wisconsin's Wartime Gift To Michigan, Living Up to Notices". The Owosso Argus-Press.

"Michigan Defeats Illinois, 42 to 6: Daley, in Last Game With the Wolverines, Scores Two Touchdowns; Hirsch Also a Factor". The New York Times (AP story). October 31, 1943.

"Hirsch Is Standout as Michigan Wins: Former Badger Back Scores Pair of Touchdowns in 26–0 Victory Over Camp Grant". The Milwaukee Journal (AP story). September 19, 1943.[permanent dead link]

John N. Sabo (October 24, 1943). "Dr. Elroy Hirsch Provides Medicine for What Has Been Ailing Michigan". Detroit Free Press. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Elroy Hirsch Stars as Michigan Leads Minnesota, 28 to 6". The Milwaukee Journal. October 23, 1943.[permanent dead link]

Bruce Madej; Rob Toonkel; Mike Pearson; Greg Kinney (1997). Michigan: Champions of the West. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 99. ISBN 1-57167-115-3.

Len Wagner (April 6, 1969). "He wasn't sure he really wanted the UW job (part 2)". Green Bay Press-Gazette. pp. 2–4.

"We Give You Mr. Elroy Hirsch, Star of Two Sports in One Day". Detroit Free Press. May 14, 1944. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Elroy Hirsch Sent To Parris Island". The Daily Plainsman. June 9, 1944. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Marines Uncover A Star Player". The Morning Herald (Hagerstown, MD). November 10, 1944. p. 28 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Cleveland Picks Hirsch in Draft". The Rhinelander (Wis.) Daily News. April 7, 1945. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Highlights in Sports". Clarion-Ledger. May 28, 1945. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"El Toro Mops Up Bombers: Elroy Hirsch Sparks Marines to 20–9 Win as Sinkwich Injured". Los Angeles Times. October 15, 1945. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"El Toro Marines Swamp Bulldogs". Nevada State Journal. September 23, 1945. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Elroy Hirsch Will Not Play Baseball". The Daily Mail (Hagerstown, MD). May 18, 1946. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Braven Dyer (August 24, 1946). "All-Stars Upset Rams, 16–0, To Stun 97,380: Hirsch Registers Two Touchdowns to Spill National Pro Champs". Los Angeles Times. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Elroy Hirsch Refuses To Sign Contract With Cleveland Club". Green Bay Press-Gazette. May 28, 1945. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Chicago Hornets/Rockets Franchise Encyclopedia". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

"Ratterman's Four Tosses Foil Rockets". The Des Moines Register. September 20, 1947. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Rockets' Elroy Hirsch Claims Highest-Paid Water Boy Title". The Daily Tar Heel. December 4, 1947. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Grid Ace Suffers Fractured Skull: Elroy Hirsch Injured Sunday May Be Out for Rest of Year". The Salt Lake Tribune. September 30, 1948. p. 20 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Packers Or Not at All: Hirsch Claims Hornets Broke His Contract; Approached Packers Because He Wasn't Paid Bonus". Green Bay Press-Gazette. June 3, 1949. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Los Angeles Rams Sign Halfback Elroy Hirsch". Wilmington (DE) Morning News. July 27, 1949. p. 30 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Bob Oates (February 7, 1988). "Difference of Distance: Despite Jerry Rice's Big Season in '87, Crazylegs Hirsch, Now 64, Remains the King of the Successful Long Pass". Los Angeles Times. p. III-3.

Frank Finch (September 24, 1949). "Rams Capture 27–24 Thriller". Los Angeles Times. p. 33 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

John Grasso (2013). Historical Dictionary of Football. Scarecrow Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-8108-7857-0.

"Sports Hot Line". The Cincinnati Enquirer. January 23, 1975. p. 48 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Dutch Treat". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

"1951 Los Angeles Rams Statistics & Players". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

"NFL Single-Season Receiving Yards Leaders". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 19, 2016.(At the time of the merger, no NFL player had matched Hirsch's single-season record. However, two AFL players [ Charlie Hennigan in 1961 and 1964 and Lance Alworth in 1965] had exceeded Hirsch's mark, and those totals were merged into the NFL record book at the time of the merger.)

"NFL Single-Season Receiving Yards per Game Leaders". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

"NFL Single-Season Receiving Touchdowns Leaders". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

Bob Oates (February 7, 1988). "Difference of Distance: Despite Jerry Rice's Big Season in '87, Crazylegs Hirsch, Now 64, Remains the King of the Successful Long Pass (part 2)". Los Angeles Times. p. III-13.

"NFL Year-by-Year Receptions Leaders". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

Earl Wright (December 21, 1951). "Otto Graham Is Selected by United Press as Pro Football Player of Year". The Berkshire (MA) Evening Eagle. p. 22 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Elroy Hirsch Calls It Career at 34 To Become Youth Program Director". Green Bay Press-Gazette. January 15, 1958. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Dick Hyland (January 15, 1958). "Elroy Hirsch Quits Football for TV Position". Los Angeles Times. p. IV1–IV2 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Bob Kelly Says . . ". The Independent (Long Beach, CA). August 22, 1958. p. C3 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Press Release". University of Wisconsin News and Publication Service. March 15, 1972.

"'Crazylegs,' Story of Hirsch, Rivoli Theater Feature Film". The La Crosse (WI) Sunday Tribune. November 15, 1953. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Crazylegs". Hall Bartlett Productions, Inc. 1953. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016.

"Crazylegs: Hollywood cemented Elroy's fame". Wisconsin Week. July 29, 1987.

"Attempts Escape From Barless Prison". The Salina Journal. July 10, 1955. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Gloria B. Anderson (January 29, 2004). "Wisconsin loses a legend: Elroy 'Crazylegs' Hirsch, 1923–2004; 'He loved the Badgers'". Green Bay (WI) Press-Gazette. p. C1 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Out Of Context Cinema: Zero Hour!". WFMU. September 27, 2007.(includes 10 minutes of clips featuring Hirsch)

"Captain Midnight Ovaltine advertisement". Captain Midnight. 1956. Archived from the original on January 2, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

Nick at Nite's Classic TV Companion, edited by Tom Hill, copyright 1996 by Viacom International, p. 370

Stephen Cox; Yvonne DeCarlo; Butch Patrick (2006). The Munsters: A Trip Down Mockingbird Lane. Watson-Guptill Publications. p. 190. ISBN 0-8230-7894-9.

"Crazy Legs Hirsch On The Munsters". BringBackTheLARams. April 26, 2012. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

Mal Florence (March 23, 1960). "Hirsch Named Ram General Manager". Los Angeles Times. p. IV1 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Cleveland/St. Louis/LA Rams Franchise Encyclopedia". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

"Elroy Hirsch Takes Job As U. of Wisconsin AD". The Sun-Telegram (San Bernardino). March 1, 1969. p. A8 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Ross, J. R. (January 31, 2004). "Elroy 'Crazy Legs' Hirsch; Rams player had running style". The Boston Globe. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

"Crazylegs: End of Hirsch reign shows need for more than cheerleading". Green Bay Press-Gazette. June 29, 1987. p. A8 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Crazy Legs Hirsch to step down". The New Mexican (Santa Fe). December 27, 1986. p. B2 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Hirsch will do UW football color". Green Bay Press-Gazette. July 8, 1997. p. C6 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"#87: Elroy "Crazy legs" Hirsch: The Top 100 NFL's Greatest Players". NFL Films. 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

"Elroy Hirsch Named to NFL Hall of Fame". Los Angeles Times. February 20, 1968. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Elroy Hirsch Piked To Grid Hall of Fame". La Crosse (WI) Tribune. April 12, 1974. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Night Train Lane Picked On Pros' All-Time Team". Detroit Free Press. September 7, 1969. p. 3E – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Graham, Huff on All-1950s Pro Football Selections". Racine Sunday Bulletin. August 31, 1969. p. 6C – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Elroy Hirsch Gains State Hall of Fame". The Daily Telegram (Eau-Claire, WI). November 28, 1964. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Lists". Democrat and Chronicle. January 24, 1992. p. 2D – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor". University of Michigan, Bentley Historical Library. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

"Rams' All-Time Team". Los Angeles Times. September 17, 1986. p. IIID – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"The Street of Broken Tackles". Chicago Tribune. September 11, 1987.

"Press Release: Hirsch's No. 40 Retired". University of Wisconsin Sports News Service. November 21, 1987.

"Football dominates Hall of Fame pick". Battle Creek (MI) Enquirer. July 9, 1988. p. 3C – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"untitled". Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY). August 15, 1999. p. 3D – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"A Great Player, but a Better Nickname". Los Angeles Times. May 20, 2005. p. D2 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

Kravitz, Bob (July 11, 2021). "NFL 100: At No. 94, Elroy 'Crazylegs' Hirsch was 'the embodiment of swivel-hipness'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

"Race Information". Crazylegs Classic. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

"North Side Relatives ... Where's Bliss ..." Green Bay Press-Gazette. June 28, 1946. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com. Open access icon

"Ruth Hirsch Obituary". Wausau Daily Herald. August 6, 2011.

Karen Walsh (July 29, 1987). "Ruth and Elroy: A good 41 year". Wisconsin Week.

"Badgers have faithful fan in Mrs. Elroy Hirsch". The Daily Tribune, Wisconsin Rapids (AP story). August 26, 1969. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.