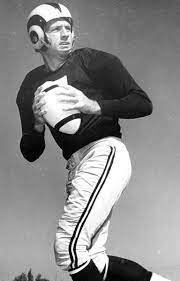

Otto Everett Graham Jr. was an American professional football player who was a quarterback for the Cleveland Browns in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) and National Football League . Graham is regarded by critics as one of the most dominant players of his era, having taken the Browns to league championship games every year between 1946 and 1955, making ten championship appearances, and winning seven of them. With Graham at quarterback, the Browns posted a record of 57 wins, 13 losses, and one tie, including a 9–3 win–loss record in the playoffs. He holds the NFL record for career average yards gained per pass attempt, with 8.63. He also holds the record for the highest career winning percentage for an NFL starting quarterback, at 0.810. Long-time New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, a friend of Graham's, once called him "as great of a quarterback as there ever was."

Graham grew up in Waukegan, Illinois, the son of music teachers. He entered Northwestern University in 1940 on a basketball scholarship, but football soon became his main sport. After a brief stint in the military at the end of World War II, Graham played for the Rochester Royals of the National Basketball League (NBL), winning the 1945–46 championship. Paul Brown, Cleveland's coach, signed Graham to play for the Browns, where he thrived. Graham's 1946 NBL and AAFC titles made him the first of only two people to have won championships in two of the four major North American sports (the second was Gene Conley). After he retired from playing football in 1955, Graham coached college teams in the College All-Star Game and became head football coach for the Coast Guard Bears at the United States Coast Guard Academy. After seven years there, he was hired as head coach of the Washington Redskins in 1966. Following three unsuccessful years with them, he resigned and returned to the Coast Guard Academy, where he served as athletic director until his retirement in 1984. He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1965.

By the time Graham was discharged from the Navy late in the summer of 1946, training camp for Brown's new team, the Cleveland Browns, had already begun. Concerned that Graham was not ready to start, Brown put in Cliff Lewis at quarterback in the first game of the season. Graham, however, soon replaced Lewis in Brown's T formation offense. Handing the ball to fullback Marion Motley and throwing to ends Dante Lavelli and Mac Speedie, Graham led the team to a 12–2 regular-season record and a spot in the championship game against the AAFC's New York Yankees. The Browns won that game, touching off a period of dominance. The team won each of the AAFC's four championships between 1946 and 1949, and had professional football's second perfect season in 1948 by finishing undefeated and untied. By doing this the Browns became pro football's first undefeated championship team. Between 1947 and 1949 the Browns played 29 consecutive games without a defeat.

Graham's play was crucial to Cleveland's success. He averaged 10.5 yards per pass and had a quarterback rating of 112.1 in 1946, a professional football record until Joe Montana surpassed it in 1989. Graham was named the AAFC's Most Valuable Player in 1947 and shared the Most Valuable Player award with Frankie Albert of the San Francisco 49ers in 1948. He led the league in passing yards between 1947 and 1949. The AAFC dissolved after the 1949 season, and three of its teams, including the Browns, merged into the more established National Football League. Graham was the AAFC's all-time leading passer, throwing for 10,085 yards and 86 touchdowns.

Graham became the Browns' uncontested leader, but he was also "just one of the guys", tackle Mike McCormack said in 1999. "He was not aloof, which you see a lot of times today." He was good at spinning and moving in the pocket, skills he learned playing basketball. In his autobiography, Paul Brown praised Graham's ability to anticipate his receivers' route-running by watching their shoulders. "I remember his tremendous peripheral vision and his great athletic skill, as well as his ability to throw a football far and accurately with just a flick of his arm", Brown said. His short passes were hard and accurate, teammates later said, and his long balls were soft. "I used to catch a lot of them one-handed", Lavelli said. "He had great touch in his hands." He was nicknamed "Automatic Otto" for his consistency and toughness.

With Graham at the helm, the Browns continued to succeed when they joined the NFL in 1950. Graham led the Browns to a 10–2 record, which set up a playoff against the New York Giants for a spot in the championship game. The Browns' only two losses of the season had come against the Giants, but in a frozen Cleveland Stadium on December 17, Cleveland beat New York. With the game tied 3–3 in the fourth quarter, Graham gained 45 yards by running with the ball on a long drive to set up a 28-yard Lou Groza field goal that put the Browns ahead 6–3. A safety after the ensuing kickoff made the final score 8–3.

The win put Cleveland in the NFL championship game against the Los Angeles Rams. Graham's rushing and passing were again key to the Browns' 30–28 victory. He drove the offense downfield as time expired to set up a last-minute Groza field goal that sealed the win. Graham had 99 yards rushing in the game, adding 298 yards of passing and four touchdowns.

Cleveland posted an 11–1 record in 1951, losing their only game to the San Francisco 49ers in the season opener. That gave the Browns another spot in the championship game, again against the Rams. This time, however, the Rams won 24–17. Graham fumbled the ball in the third quarter, setting up a touchdown that put the Rams ahead 14–10. Three of his throws were intercepted, but he put up 280 yards of passing and a touchdown. After the season, Graham was named the league's Most Valuable Player.

With Graham at quarterback, Cleveland finished the 1952 season with a 9–3 record and faced the Detroit Lions in the NFL championship game. Despite gaining 384 total yards to Detroit's 258, Graham and the Browns lost their second straight championship, 17–7. Cleveland had several long drives that ended with missed field goals, and a fourth-quarter touchdown was negated because Graham's throw to Pete Brewster was first tipped by receiver Ray Renfro; under rules in place at the time, balls deflected by offensive teammates were automatic incompletions. After the season, as Graham was practicing for the Pro Bowl in Los Angeles on January 2, 1953, his six-week-old son Stephen died from a severe cold.

The 1953 season began with a 27–0 win over the Green Bay Packers in which Graham passed for 292 yards and ran for two touchdowns. It was the first of 11 straight victories for the Browns, whose only loss came in the final game of the season to the Philadelphia Eagles. Near the end of the season in a game against the 49ers, Graham took a forearm to the face from Art Michalik that opened a gash on his chin requiring 15 stitches. Graham's helmet was fitted with a clear plastic face mask, and he came back into the game; the injury helped inspire the development of the modern face mask. Despite an 11–1 record, Cleveland lost in the championship game for the third year in a row, falling to the Detroit Lions 17–16. Two of Graham's passes were intercepted. He said after the game that he wanted to "jump off a building" for letting his teammates down. "I was the main factor in losing", he said. "If I had played my usual game, we would have won." Still, Graham finished the season as the NFL's leading passer and again won the Most Valuable Player award.

Before the start of the Browns' 1954 training camp, Graham was questioned as part of the Sam Sheppard murder case. Sheppard, an osteopath, was accused of bludgeoning his pregnant wife to death, and Graham and his wife, Beverly, were friends with the couple. Graham told police that while he and Beverly liked the Sheppards, they did not know much about their relationship.

The 1954 season was a transitional one for the Browns. Many of the players who joined the 1946 team had retired or were nearing the end of their careers. Graham, meanwhile, told Brown that he would retire after the season. After losing the first three games, Cleveland won eight in a row and earned another shot at the championship, again against the Lions. This time, the Browns won 56–10 as Graham ran for three touchdowns and passed for three more. He announced his retirement after the game.

After Graham's potential replacements struggled during the 1955 training camp and preseason, Brown convinced Graham to come back and play one more year. He was offered a salary of $25,000 ($250,000 today), making him the highest-paid player in the NFL. The Browns lost the opener against the Washington Redskins, but went on to a 9–2–1 regular-season record and another chance at a championship. Graham threw two touchdowns and ran for two more as the Browns beat the Rams 38–14. When Brown took Graham out of the game in the fourth quarter, the crowd in the Los Angeles Coliseum gave him a standing ovation. It was the final performance of a 10-year career in which Graham's team reached the championship each year and won seven. "Nothing would induce me to come back", he said later. He was the NFL's passing leader and Most Valuable Player in 1955. He also won the Hickok Belt, awarded to the best professional athlete of the year. Without Graham, the Browns floundered the following year and posted a 5–7 record, their first-ever losing season.

Graham and head coach Paul Brown created the modern T-formation quarterback position and the modern pro offense. Graham led his league in every major passing category each in multiple seasons and finished his career with a career all-time pro record Yds/Att of 9.0. Until a few years ago he held the record for career rushing touchdowns by a pro quarterback with 44. The Browns' record with Graham as starting quarterback was 57–13–1, including a 9–3 record in the playoffs. He still holds the NFL career record for yards per pass attempt, averaging 8.63. He also holds the record for the highest career winning percentage for an NFL starting quarterback, with 0.810. Graham was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1965. Having won seven championships in 10 seasons and reached the championship game in every year he played, Graham is regarded by sportswriters as one of the greatest winners of all time and one of the best professional quarterbacks ever to play the game. He never missed a game in his career.

Graham wore number 60 for much of his career, but he was forced to change it to 14 in 1952 after the NFL passed a rule requiring offensive linemen to wear jersey numbers 50–79 so referees could more easily identify ineligible receivers. The Browns retired his number 14, while 60 remains in circulation. While at Northwestern, Graham wore number 48.

When Graham retired from football, he planned to focus on managing the insurance and appliance businesses he owned. However, in 1957 Graham signed on as an assistant coach for the college squad in the annual College All-Star Game, a now-defunct exhibition contest between the NFL champion and a selection of the best collegiate players from around the country. The next year, he was named head coach of the team. With Graham coaching the all-stars in 1958, the team beat the Detroit Lions 35–19.

Following his convincing win in the all-star game, Graham's friend George Steinbrenner helped get him a job as the head football coach for the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. Graham, by then 37 years old, was also named athletic director and given a salary "in five figures". School officials said the hiring did not mean Coast Guard would "go big time"; the Division III school played a relatively short schedule at the time against smaller schools in New England. The Coast Guard team had a 3–5 record in Graham's first year as coach in 1959, but improved steadily over the ensuing three years. The team went undefeated in 1963, earning the academy its first-ever post-season bowl appearance. Coast Guard lost to Western Kentucky 27–0 in the Tangerine Bowl. Graham continued to coach in the College All-Star Game while at Coast Guard, and his college team beat Vince Lombardi's Green Bay Packers in a 20–17 upset in 1963. Graham was offered coaching jobs in the NFL numerous times during his tenure at Coast Guard, but he said in 1964 that he was content to stay at the small school on a $9,000 salary. He said he deplored the "win at all costs philosophy" that was necessary to be successful in the professional ranks.

Despite his reservations about the professional game, Graham, who moonlighted as a television and radio commentator for the American Football League's New York Jets in 1964 and 1965, left the Coast Guard Academy after seven years in 1966 to become head coach and general manager of the NFL's Washington Redskins, Graham's three seasons (1966–1968) were similarly unsuccessful, with an overall record of 17–22–3. In 1968, calls for his firing had intensified as the team's performance worsened from 7–7 in 1967 to 5–9; The Washington Daily News called for his firing in a front-page editorial in November. Vince Lombardi took over as the Redskins' head coach in 1969.

After being dismissed as the Redskins' coach, Graham returned to the Coast Guard Academy as athletic director and said he planned to stay there until he retired. He coached the college team in the College All-Star Game in 1970 for his tenth and final time. The college stars lost for the seventh time in a row that year, falling 24–3 to the Kansas City Chiefs. He was replaced in 1971 by Blanton Collier, who had retired after succeeding Brown as Cleveland's head coach.

In 1974, Graham was named Coast Guard's football coach once again, although he resigned two years later to focus on his duties as athletic director. In nine years of coaching, Graham's Coast Guard teams had a combined record of 44–32–1. After eight more years as the school's athletic director, Graham retired in 1984.