Csonka was the No. 1 pick by the American Football League's Miami Dolphins in the 1968 Common Draft, the eighth player and first running back drafted in the first round. He signed a three-year contract that paid him a signing bonus of $34,000 (equivalent to $286,000 in 2022) and a car, and a salary of $20,000 (equivalent to $168,000 in 2022), then $25,000 (equivalent to $210,000 in 2022), then $30,000 (equivalent to $252,000 in 2022) each year.

Csonka's pro career got off to a shaky start. In the fifth game of the 1968 season, at home against Buffalo, he was knocked out and suffered a concussion when his head hit the ground during a tackle. He spent two days in the hospital. Three weeks later at San Diego, he suffered another concussion, plus a ruptured eardrum and a broken nose.[6] There was talk he might have to give up football. He missed three games in 1968 and three more in 1969. Writes his teammate Nick Buoniconti,

There was some question [after the 1969 season] whether Csonka would ever play fullback again—not just because of injuries but because he didn't play well ... When Shula came in [in 1970] he literally had to teach Csonka how to run with the football. He used to run straight up and down and Shula impressed upon him that he had to lead with his forearm rather than his head. Shula and his backfield coach Carl Taseff basically reengineered Csonka to where he became the Hall of Fame player. Csonka emerged as the offensive leader of the Dolphins.

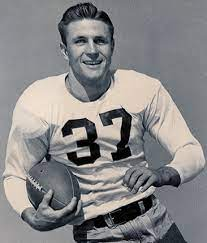

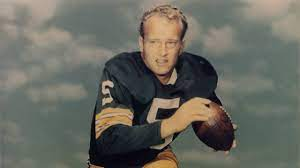

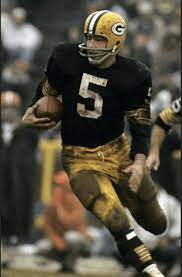

Over the next four seasons, Csonka never missed a game, and he led the Dolphins in rushing the next five seasons. Writes teammate Jim Langer, "Csonka had the utmost respect of every player on the team, offense and defense." By the 1970s he was one of the most feared runners in professional football. Standing 6 feet, 3 inches and 235 pounds, he was one of the biggest running backs of his day and pounded through the middle of the field with relative ease, often dragging tacklers 5–10 yards. He was described as a bulldozer or battering ram. His running style reminded people of a legendary power runner from the 1930s, Bronko Nagurski. Said Minnesota Vikings linebacker Jeff Siemon after Super Bowl VIII, "It's not the collision that gets you. It's what happens after you tackle him. His legs are just so strong he keeps moving. He carries you. He's a movable weight." He rarely fumbled the ball or dropped a pass, and he was an excellent blocker.

Stories abound about Csonka's toughness. He broke his nose about ten times playing football in high school, college, and the pros, causing it to be permanently deformed, and he would remain in the game with blood pouring out of it. He may be the only running back to receive a personal foul for unnecessary roughness while running the ball, when, in a game against the Buffalo Bills in 1970, he knocked out safety John Pitts with a forearm shot that was more like a right cross. In a close game against the Minnesota Vikings in the perfect season of 1972, Csonka was hit in the back by linebacker Roy Winston in a tackle so grotesque it was shown on The Tonight Show. Csonka thought his back was broken and he actually crawled off the field. Once on the sideline, he "walked it off" and in a few minutes was back in the game. His return to the game was crucial, as the winning touchdown pass to tight end Jim Mandich was set up by a fake to Csonka. He was named the 10th toughest football player of all time in the 1996 NFL Films production The NFL's 100 Toughest Players. Dolphins' offensive line coach Monte Clark was asked about Csonka's bruising running style, and he responded, "When Csonka goes on safari, the lions roll up their windows."

The Dolphins had one of professional football's best rushing attacks in the early 1970s. The Dolphins led the NFL in rushing in 1971 and 1972, setting a new rushing record in 1972 at 2,960 yards. Csonka's 1,117 yards that season combined with Mercury Morris contributing exactly 1,000 yards made them the first 1,000 yard rushing duo in NFL history. That rushing attack led the Dolphins to Super Bowls VI, VII, and VIII, with victories in the last two. Csonka's powerful running style set the tone for the ball-control Dolphins. He chose to run through defenders instead of around them, leading to three straight 1,000-yard seasons (1971–1973) and two seasons (1971–1972) in which he averaged more than 5 yards per carry, amazing for a fullback. His 5.4 yards per carry average in 1971 led the NFL. Teammate Bob Kuechenberg said that Csonka was the best back he ever saw for turning a 2-yard gain into a 5-yard gain. "The line got him the start, he got the finish and it added up to 4 or 5 yards every time," said Kuechenberg. Csonka's 1971 season was also the only year in the 1970s that a running back gained over 1,000 rushing yards without a single fumble.

During the 1971 off season Csonka starred in the critically well received off Broadway play of"Larry Csonka and the Chocolate Factory.” Due to financial backing and Larry's contract with the Dolphins barring him from any off season "strenuous activity" the play never gained commercial success, but for his efforts Csonka was nominated in the 1972 Obie Award for best Actor, where he eventually lost to Douglas Rain for his role in Vivat!Vivat Regina!

During the 1972 season, the Dolphins became the only team since the AFL–NFL Merger to go undefeated, and Csonka was an instrumental part of the success, rushing for a career-best 1,117 yards. Csonka led all rushers in Super Bowl VII with 112 yards on only 15 carries. Late in the third quarter, Csonka had a run that epitomized his style. After breaking several tackles near the line of scrimmage, he rumbled for 49 yards. Near the end of that run, Washington Redskins cornerback Pat Fischer, who was known as a fearless and gritty tackler, came up to try to tackle Csonka. Instead of trying to avoid Fischer, Csonka actually turned toward him and threw a forearm at him, brushing the 175-pound Fischer aside.

In 1973, Csonka was voted Super Athlete of the Year by the Professional Football Writers Association. That season, the Dolphins won a second straight title and "Zonk", as he was known, was the Super Bowl VIII MVP. Exploiting brilliant blocking by his offensive line, he rushed 33 times for two touchdowns and a then-record 145 yards.

Csonka and his friend, Dolphins running back Jim Kiick, were known as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The August 7, 1972 issue of Sports Illustrated featured a profile of Csonka and Kiick. This issue has become a collector's item because of the cover photograph of Csonka and Kiick by famed Sports Illustrated photographer Walter Iooss, with Csonka (inadvertently) making an obscene gesture with the middle finger of his right hand. In 1973, Csonka and Kiick, in collaboration with sportswriter Dave Anderson, wrote a book, Always on the Run. (A second edition, with an additional chapter covering the 1973 season, Super Bowl VIII, and their signing with the World Football League was published in 1974.) Csonka and Kiick discuss their childhoods, their college football careers, their sometimes stormy relationship with Don Shula, their experiences as pro football players, and the sometimes outrageous behavior of their teammates. The book provides insight into the history of the Dolphins and the state of pro football in the late 1960s and early and mid-1970s.

In March 1974, he was selected second overall in the WFL Pro Draft. The same month, Csonka, Kiick, and Dolphin wide receiver Paul Warfield, announced they had signed contracts to play in the fledgling World Football League starting in 1975. Csonka signed a three-year guaranteed contract for a salary of $1.4 million. While their signings are credited with giving the WFL credibility, the league was plagued by financial problems from its start. The three played for the Memphis Southmen, but Csonka and the others had minimal success and the league folded midway through its second season. Csonka carried the ball 99 times for 421 yards for 1 touchdown for Memphis in 1975.

A free agent again, he joined the New York Giants in 1976, along with Memphis coach John McVay. (The Giants' head coach at the time was Bill Arnsparger, who had previously been the Dolphins' defensive coordinator.) He tore ligaments in his knee, prematurely ending his first season there. He blamed the injury in part on Giants Stadium's artificial turf, and has been a vocal critic of the surface and its injury potential ever since, (The Giants currently use a newer, more flexible Fieldturf). When the Giants started the season 0–7, Arnsparger was fired and replaced by McVay.

Two seasons later, he was on the field for The Miracle at the Meadowlands, the play that for years epitomized Giants' fans exasperation with the franchise's long-term mediocrity. On November 19, 1978, New York had apparently secured a 17–12 victory over the favored Philadelphia Eagles. However, with 31 seconds left to play and the Eagles out of timeouts, offensive coordinator Bob Gibson overruled quarterback Joe Pisarcik and called for the ball to be handed off to Csonka for a run up the middle, as Gibson felt Pisarcik was risking too much injury falling on the ball in an era before the quarterback kneel to run out the clock was common. However, Pisarcik botched the handoff and Eagles cornerback Herman Edwards returned the fumbled ball 29 yards for the winning touchdown. The Giants went into a tailspin afterwards, and finished 6–10 after a hopeful start.

The Giants let McVay go after the season ended. Csonka's contract was up, too, and he returned to Miami the next year. He ran for over 800 yards, his best since their Super Bowl days, and rushed for a career-high 12 touchdowns while catching one more. Csonka won Comeback Player of the Year for his 1979 season. Unable to come to terms with the Dolphins on a new contract, he retired after the year was over.

In his 11 NFL seasons, Csonka carried the ball 1,891 times for 8,081 yards and 64 touchdowns. He also caught 106 passes for 820 yards and four touchdowns. He was among the NFL's top 10 ranked players in rushing yards four times, in rushing touchdowns five times, total touchdowns three times and yards from the line of scrimmage once. He earned All-AFC honors four times and was named All-Pro in 1971, 1972, and 1973. He was also selected to play in five Pro Bowls.

Since his retirement, he has become a motivational speaker and has hosted several hunting and fishing shows for the NBC Sports Network (formerly OLN and Versus). Csonka has been featured in many shows, such as The Ed Sullivan Show, and had a role in the 1970s medical drama Emergency! He played the part of commander Delaney in the 1976 movie Midway. He worked for the United States Football League (USFL) Jacksonville Bulls in the mid-1980s, first as director of scouting and then as general manager. Csonka was also a color analyst for NFL games on NBC in 1988, and an analyst for the syndicated show American Gladiators from 1990 to 1993 (seasons 2 through 4).

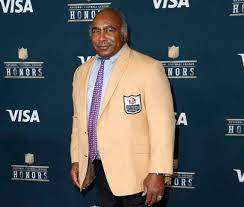

Csonka was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1987 and his #39 was retired by the Miami Dolphins in 2002. He is one of 11 Dolphins (Jim Langer, Bob Griese, Paul Warfield, Larry Little, Dwight Stephenson, Nick Buoniconti, Jason Taylor, Dan Marino, Don Shula and Zach Thomas) in the Hall of Fame. Csonka was named a member of the Super Bowl Dream Team in an NFL Films production.

Between 1985 and 1990 Csonka started spending time in Alaska, eventually living most of the year in Anchorage. While observing the 1,161-mile (1,962-km) 2005 Iditarod dog sled race he said, "when I was playing and practicing in that heat in July and August in Miami with shoulder pads on, it just vaporized me".

From 1998 through 2013, Csonka was producer and co-host of Napa's North to Alaska, before retiring the show. Csonka also did Csonka Outdoors, 1998–2005 on ESPN-2 and OLN. In early September 2005, Csonka and five others were returning by boat to the village of Nikolski on Umnak Island in Alaska's Aleutian Islands after filming a reindeer hunt on the island for Csonka's TV show, North to Alaska. The boat was caught in a severe storm and nearly capsized. They rode out the storm for 10 hours before a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter could reach them and rescue them one-by-one in a basket.

Csonka and North to Alaska co-host Audrey Bradshaw currently live in Wasilla, Alaska. He also maintains a farm in Lisbon, Ohio and operates Goodrich Seafood House in Oak Hill, Florida. Csonka currently appears in television commercials for the Alaska Spine Institute, an Anchorage-based physical rehabilitation center.

In November 2013, Csonka was recognized by the Pro Football Hall of Fame as part of "Hometown Hall of Famers," a national program honoring the hometown roots of the sport's greatest coaches, players and contributors with special ceremonies and plaque dedication events in local communities. Csonka was presented with a plaque during a ceremony in the Stow High School gym, where the plaque will stay permanently to serve as an inspiration for the school's students and athletes.

Csonka played a fictional version of himself in the HBO series Ballers and was named head coach of the Miami Dolphins. He also made a cameo with Dolphins legendary former head coach, Don Shula, during a fishing trip.

In 2022, he released a memoir titled Head On.